What we learned from designing and hosting the course ‘Climate Adaptation for Creatives’

Dr Natalia Eernstman, Director of Public Education at Black Mountains College

From October 2024 to March 2025, Black Mountains College hosted a course for creative practitioners from across the UK and wider Europe, representing countries such as Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Georgia, Kazakhstan, North Macedonia, Serbia, Turkey, Ukraine, and Uzbekistan.

Commissioned by the British Council, Climate Adaptation for Creatives was designed to empower artists and creative professionals to lead climate action within their communities. This year, we offered the course to an inaugural cohort of 50 participants. A team of three tutors -Magda Petford, Andrew Hilling, and Natalia Eernstman- guided the group through a 20‑week learning journey. The program combined independent study with bi‑weekly interactive live sessions; participants also accessed bespoke podcasts and videos, and collaborated to explore the role of the arts and their own practice in climate and environmental action.

The pilot tested how BMC’s experiential, place‑based pedagogy could translate into an online setting. Drawing on participant feedback and tutor reflections, what follows shares the key learnings, and offers wider perspectives on education, activism, systems change, and the role of art in a time of climate emergency.

(Before you dive into the article, I invite you to scroll down and read the postscript. It offers relevant context to the ideas explored here. But if you prefer to continue reading straight through, you will encounter those insights naturally along the way.)

Creating a Soulful, Creative, and Experiential Online Learning Experience

To ensure the course reflected the needs of participants, we spoke with over 90 creative practitioners from the Wider Europe region. We also partnered with digital learning design experts Wellknown to adapt BMC’s core pedagogical values for an online setting.

The virtual classroom can feel at odds with BMC’s approach. Neuroscience tells us humans learn with all their senses, storing memories throughout the body. At our campus in the Bannau Brycheiniog National Park, the land, farm, and local community become classrooms, with students learning through direct engagement, practice and real-world contexts. Online tools, such as break‑out rooms, whiteboards and quizzes, offer useful interaction but rarely match the depth of embodied, experiential learning. As a result, many virtual trainings risk feeling formulaic and uninspiring. We therefore made engaging participants’ whole selves -body, mind, heart, and hands- a core design priority.

Stories, images, and metaphors reach beyond intellect into the emotional and subconscious, giving learning more depth and ‘soul’. We chose the earth’s water cycle as a narrative vessel for the course, with stages like source, river, delta, distributaries, ocean, and clouds serving as metaphors for each chapter. The course opened at The Source, where participants connected as a community and shared their starting points: their motivations for joining the course and their hopes for it. For their first task, they visited their nearest body of water while listening to an audio piece introducing the course narrative. They took a photo, pinned it on our online platform, and described a personal quality they shared with that body of water. These poetic self‑portraits -lakes, shorelines, ponds- helped participants connect across borders and cultural differences while grounding the course in each person’s local context.

“I always find similarity between me and the Caspian Sea. We are both calm on the surface, yet beneath lies a world of depth, rich with metaphors, images, and countless realities. Just as the sea listens to the winds and reflects the sky while holding its own mystery, so do I—always ready to listen, reflecting the world around me.”

— Poet Leyli Salayeva

Independent study resources included audio journeys crafted with sound artist Jo Barratt. One piece guided participants into an immersive space where they explored climate change through the personal narrative of scientist James Dyke. They were invited to walk through their environment, map projected climate impacts on local ecologies and systems.

Participants valued these experiential resources for offering more than content: they created space to pause, listen, reflect, and relate. One participant described the experience as “Blocking this time every two weeks to allow space for new acquaintances or possibilities without the pressure of expecting too much.” Another noted that it allowed them “space to do something different.” For us as tutors, it became clear that time -dedicated, protected space- was a defining ingredient in the learning process.

Time to Transform

Time today is currency and power; something tech companies know well as they design business models to capture and monetise our attention. It is a precious commodity, yet also one of the most potent levers for change. What we choose to give our attention to shapes the very systems we inhabit. Thinkers like Bayo Akomolafe invite us to consider “slowing down” as a radical act -particularly in moments when urgency is amplified by newspaper headlines, mounting crises, and calls to action.

As educators at a college that aims to prepare as many people as possible for a climate crisis that has effectively already happened, this course emerged from a similar sense of urgency. Yet, when faced with a cohort of ambitious, passionate practitioners, we saw how stretched thin they were: balancing professional work, artistic practice, family and community responsibilities, and -in some cases- navigating war, political instability, or power outages. Our assignments and two‑hour live sessions risked becoming yet another obligation in their already overburdened life.

This dichotomy became a recurring theme during our tutor reflective meetings. And through my own experience of continuously feeling pressed for time, I landed on the (admittedly rather unimaginative) metaphor of a hamster wheel. It represents the perpetual spin of modern life -earning a living, organising events and projects, seeking grant funding, attending the events organised by others, care duties, more projects- propelled by its own relentless momentum. Whether we like it or not, we are active participants in creating the wheel-system that determines how we live. It sustains livelihoods and fuels purpose, but it also traps us in patterns we rarely have the time to question. Patterns that are largely rooted in unsustainable capitalist narratives that we –often through our running- are trying to change. And as the wheel is places in a destabilising world, with rising costs, institutional cutbacks, and ever‑louder calls for urgent climate action, the instinct is to run faster. But the faster we run, the more we propel the wheel and the harder it is to step back and examine the wheel itself, or to ask ourselves whether we want to be running hamsters (no offence to the hamster by the way).

Here lies the paradox of transformative education: by asking more of learners -through content, tasks, and deliverables- we may be reinforcing the very systems we hope to challenge. And yet, because their time is in such limited supply, learners often arrive expecting their time will be “used well”; by being presented effective content and knowledgeable experts, and through engagement in clearly useful tasks. These expectations keep both educators and learners running in circles.

If slowing down is indeed a necessary and radical act, then perhaps the most transformative course would deliver… well, nothing. It would offer nothing but space: a deliberate pause, a clearing in which to reflect. This obviously isn’t a very tempting course offer in a culture that prizes productivity and results. How do we reconcile the need to slow down with the demand for content? And what is a course filled with, if not with that matter? How do we create a space of pause rich enough to hold curiosity and inquiry without appearing (but still being largely) empty or purposeless? And perhaps most provocatively: if the wheel itself is part of the problem, how do we step off it together -who will be there to catch us when we do?

The Dark Matter of Education

Let’s explore possible answers to these questions through another metaphor. Astronomers estimate that roughly 85% of all matter in the universe is dark matter -undetectable by current instruments- while only 15% is the ‘normal’, tangible, measurable matter we can see. My proposition is that most learning works the same way: the majority happens through invisible processes, not the visible and measurable ‘stuff’, like PowerPoints, data, books, expert presentations. This ‘dark matter of education’ is as important, if not more so, than all the visible material -especially in climate education.

Of course, there is value in understanding the science behind global warming, ecology, or systems thinking. It is useful to learn from others who have tried, failed, or succeeded, to avoid repeating mistakes. There is value in knowing the specifications of a compost toilet, the basics of growing perennials, or how to identify plants. But research shows that more knowledge about the climate crisis does not automatically lead to action: the so‑called knowledge–action gap (Räsänen et al., 2024). Knowing ecological science does not necessarily make us feel connected to or fall in love with nature enough to dedicate our lives to protecting it, just as knowing the anatomy of my children does not define my love for them.

If the purpose of climate education is to inspire action to halt warming, protect biodiversity, and build community resilience, then concepts and intellectual knowledge alone are not enough.

Similarly, while formal education focuses on tangible knowledge and testable ‘hard skills,’ employers often value ‘soft skills’ more. Organisations in all sectors rely heavily on their people’s ability to collaborate, think creatively, communicate, and manage time and stress. In this era of planetary crises, we must also equip learners with less typical but essential soft skills: staying calm under pressure, persevering despite setbacks, leading compassionately, empathy, imagination, improvisation, negotiation, and more. Establishing a food and farming co‑op, for example, depends on the ability to imagine what does not yet exist, to collaborate, engage, inspire, and navigate conflict. None of these skills can be acquired simply by watching a PowerPoint. Academic definitions of empathy or creativity may be helpful, but true learning comes from practising these skills in real situations.

It is in these spaces that the dark matter of education emerges: the socio‑emotional learning that occurs outside structured content delivery, in the moments between set tasks.

At BMC, much of this dark matter flows through the teaching of creative practice. This is partly why Art is in the title of our Degree Sustainable Futures: Art, Ecology and Systems Change. Not because we expect all students to become professional artists (though they can, and the world could use more of them), but because creative practice offers opportunities to learn things in ways that cannot be replicated elsewhere.

“The true purpose of arts education is not necessarily to create more professional dancers or artists. It is to create more complete human beings who are critical thinkers, who have curious minds, who can lead productive lives.”

– Kelly Pollock, Executive Director, COCA. Centre of Creative Arts.

It is these embodied, open‑ended experiences that teach students about themselves, their relationship to the world, and to other people. They form gateways to practising soft skills in authentic contexts. Other ‘dark matter moments’ in our Degree include walking seminars in the mountains; volunteering on our farm planting trees, weeding, and digging compost; organising community ceilidhs and running the Student Society; participating in conversations through Ways of Council; beginning each day with a ‘landing exercise’; and working on a real‑world practical project at the end of each year. These are the seemingly empty spaces not filled with structured, visible, often formulaic content, but instead full of open‑ended opportunities to pause, explore, experiment, play, try, fail, and practise soft skills unconsciously.

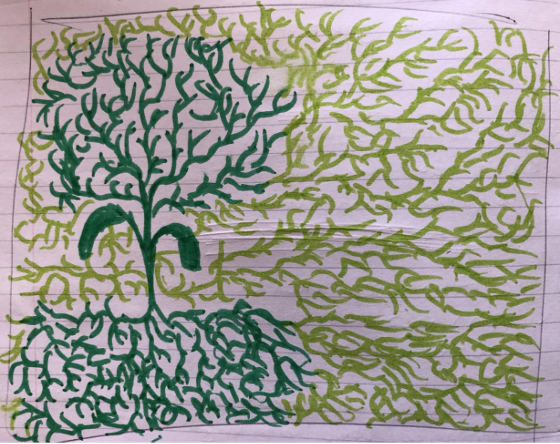

Image created by Adam, Level 4 student at BMC, when asked to depict his learning journey so far in the form of a garden.

He explained: “I am not learning straight‑up theory, but my mind is changing quite a lot.”

Sadly, since the commercialisation of education has turned learners into consumers who demand ‘value for money,’ it has become increasingly difficult to argue for educational spaces that don’t overtly deliver ‘normal,’ visible, and measurable content. This challenge formed the heart of the experiment behind designing and hosting the online course Climate Adaptation for Creatives. How do we create ‘dark matter moments’ in an online environment? And how do we coax and retain learners in these seemingly empty spaces? Here’s what we tried.

First, as explained above, many homework tasks were embodied engagements rather than purely intellectual exercises or passive absorption of content. Participants were invited to walk, listen to audio narratives curated with music and sound, be still and imagine, go out and pay attention, spend time in nature without devices, record dreams and thoughts, and have conversations with someone in their community. We did lose a few participants early on. Some politely noting they felt these activities were a waste of time. This reaction, paradoxically, demonstrated the very point we hoped to make about reassessing what constitutes a ‘good use of time’ in an age of planetary crisis. Still, we clearly failed to convince these learners of the value of such experiences and should rethink how we signpost potential benefits. Nevertheless, we retained most participants -a success in itself, given that 90% of MOOCs see learners drop out- and those who stayed went on to do remarkable things during the course.

Second, from the outset, the emphasis was on building a learning community. Live sessions were largely devoted to breakouts, with minimal tutor delivery. Participants shared reflections on homework, became critical friends to each other’s practice, and found natural ways to connect. One participant expressed their gratitude: “A special thank you for creating opportunities to learn from experts and from each other, for your attention to every participant, and for fostering a community where sharing ideas and finding like-minded people felt so natural.”

Finally, during half of the course, the tutor team delivered no formal content at all. Instead, participants worked on their own practical projects in their real‑world contexts.

The Practice of Practice

In the second half of the course, represented by the metaphor of the river flowing into a delta and branching into multiple distributaries, each participant developed a small project or intervention in response to the climate and ecological emergency. They were grouped into ‘pods’ of four to six people working on similar or complementary projects. For six weeks, these pods met regularly to reflect on progress and share what they were learning collectively. This was, in my view, the most important moment of the course, because participants were actively practising how to take action in response to the climate crisis. Undervaluing the importance of practice is a major oversight in much climate education.

After decades of climate research, multiple IPCC reports, and I-have-lost-count-so-many global climate conferences, we should have enough knowledge about causes and potential responses to act decisively. Yet little of this knowledge has translated into widespread, sustained action. Some argue that we need more certainty before acting; others believe the existing knowledge has not reached the communities where it matters most. Both points are valid, and compounded by deliberate misinformation campaigns from the fossil fuel industry to stay in business, but I would add a third reason: Western, modernised society has largely lost the skill of acting at all. An emphasis on thinking, analysing, and conceptualising has displaced the ability to act, make, move, and bring things into being. This feeds into the knowledge–action gap discussed earlier and reflects an education system rooted in epistemologies that separate mind from body and privilege abstract thought over embodied experience.

Most formal education relies heavily on the transfer of knowledge about something, rather than offering direct, lived experience. Peter Senge (Goodchild, 2021) calls this the ‘abstracting phenomenon’, where abstracted descriptions are treated as higher knowledge than lived experience. As he notes, “We struggle with how to ‘implement’ ideas because we think doing is a lesser kind of knowledge.” This has had major repercussions on how we expect to acquire knowledge, and thus how formal education systems have been constructed. With the assumption that abstracted knowledge is superior, we expect to learn about the concept first, which will then give us the knowledge necessary to implement the concept in real life. However, as Peter Senge points out: “You didn’t learn how to ‘implement walking’ when you were two years old. You learned to walk through an ongoing process of doing and discovering.” An embodied experience of trying something out and improving incrementally by further embodied experience.

These ideas are well established of course. Kolb’s experiential learning cycle roots learning in experience and reflection. Action Research generates knowledge through doing. The arts embrace practice-as-research. Donna Haraway distinguishes between the detached ‘God’s-eye view’ and the situated, embodied view from within lived experience. Yet such approaches remain fringe in dominant education models. This is a problem for three reasons: Firstly, because it undermines our capacity for climate action, as we are unable to apply the huge amount of abstracted, conceptual knowledge gathered on the matter. Secondly, because we can’t rely on the next generation to do the job either because in formal education they are taught about climate change as an abstracted concept (unsurprisingly, nearly half of Year 11 students don’t think it will affect them personally). And thirdly because the abstraction phenomenon is replicated in non-formal climate education as well.

Too often, in climate education, which is meant to inspire action, global warming is first and foremost treated as a scientific concept: abstracted from daily life and taught through data and graphs –’a fog of numbers’ (Gosh, 2021)- before moving on to secondary questions of “what can you do?”. Solutions are presented as models and examples, but the course ends with the expectation that learners will implement them in their own lives. There is little data to show whether that actually happens, but what we know from research on addiction and relapse, is that people find it very hard to change habits and routines, and that existing pressing issues usually take precedence over trying something alien or new (think: hamster, wheel, running again).

I propose that climate change education should never be an intellectual exercise isolated from land, community, food, water, livelihoods, and all the systems it touches. Like learning to walk, climate action must be taught through embodied practice. You don’t learn to play the piano by reading about it -you learn by playing it.

Despite the drive ‘to take action’ that motivates our students to enrol on the BMC Degree, I have observed that they are equally hampered by an inability to practice. They are often tentative to try something out, and prefer using the available time to debate, deliberate and plan. Many also equate value with structured content delivered by experts. That’s why, alongside ‘Change in Practice’ modules, our degree embeds creative practice modules where students “practice the practice of practice” to get comfortable with trying an idea, failing, trying again and refining it through the doing. My role is to help them find joy in the process of experimenting and making something happen without knowing exactly where it will lead, thus dissolving rigid ideas of success and failure.

The online course followed the same principle. Participants took small steps, tested, reflected, and built on their experiences. These became tangible starting points for more action, thereby incrementally improving their ability to respond and act. The results of this process were beyond anything we had hoped for. After six weeks of pod work, we had 50 distinct projects: community tree planting; an exhibition on vanishing winters in Armenia; a photography project documenting cattle farmers in Gloucester; nature-connection storytelling; immersive installations; poetry-covered oil barrels; paper from invasive plants; electric strawberries; allotment choirs; youth imagination projects; a nomadic garden in a backpack for war-torn Ukraine; a plant-centred music player; a cloud-inspired museum education programme; projects on lichen, rain, and rivers; sustainable art residencies; music hubs; films challenging cultural norms and extractivism; an arts raffle for Ukraine; ocean-debris sculptures; and a Black Sea Biennale. Many of the projects have huge potential and we are currently selecting a bunch of them to receive grants and support through a peer-mentoring program.

Margaryta Zhurunova, 2025

A Garden I Will Always Take With Me

The immense diversity, innovation and passion displayed through these projects also shows that the artists on the course slowed down enough to start reimagining the systems and narratives that shape our present realities. We would all benefit from rethinking the hamster wheel that we are on, but there is a special role for artists in this respect. One that goes beyond reproducing existing narratives through aesthetic embellishments; i.e. how can we make the hamster more aesthetic or the running more entertaining? Art should challenge the wheel. Artists display the courage to stop running, hold space for others that decide to step off, and seed alternatives in the space that opens up.

Postscript (or Foreword)

As someone who has spent a total of 21 years in regular formal education (from primary school to doctorate level) I am steeped in academic thinking and writing. This essay is both the fortunate and unfortunate result of that. Fortunate, because it has given me a superpower: the ability to abstract -extracting elements from the real world, reorganising them into neat narratives, and presenting them as useful ideas. This skill allows me to distil the complex into coherent, credible arguments, to state things with authority, and to claim fragments of knowledge as my own. Gather enough of these fragments, and one earns the label of ‘expert,’ along with the presumed right to speak and be heard (often at the expense of others who didn’t earn that right and whose voices remain unheard).

But my academic inclination is also unfortunate. Abstraction inevitably isolates certain aspects and ignores the rest, losing the richer, messier, ambiguous, and chaotic lived experience from which those aspects came. Including the whole of an experience, risks sounding incoherent, contradictory, even ‘airy‑fairy.’ So I don’t. Instead, I offer this ‘clean’ and ‘exact’ story -projecting authority, certainty, and expertise, in hopes of earning a voice in the matter.

So let me say now -whether you are about to read this essay or have just finished it- don’t be fooled by the cleanliness and certainty of this article. The lived experience behind these words was full of leaps of faith, missteps, fears, insecurities, messy human interactions, flashes of intuition, and contradictions. It was also rich with laughter, curiosity, surprise, connection, empathy, and excitement. All of that has been edited out to maintain coherence and credibility.

And if this apparent certainty leads you to believe we were ‘experts’ who knew exactly what we were doing, let me assure you, we were not. We knew some things, but not most. We know a little more now, but still not much. We are comfortable in our non‑expertise, because claiming expert status risks silencing others and replacing the joy of uncertainty with the complacency of “knowing it all.” We prefer to remain novices: excited, energised, and slightly nervous each time we teach, which also democratises the learning space.

Finally, be aware (or, if you are reading this after the essay, be slightly irritated) that this article is itself an example of the abstraction it critiques. There are other ways to share these ideas, but my academically trained mind defaulted to this form. On paper, it all sounds comfortably tidy and convincing. In practice, it is far messier, less certain, and far more interesting and exciting.

Acknowledgements

The ideas in this article would not exist in this form without ongoing conversations with Magda Petford and Andrew Hilling. I am grateful for their insight and input at every stage of the course’s design and delivery. I am equally indebted to the course participants, who trusted us enough to step into the unknown, and to the British Council (and their funders) for giving us the resources to create something new and experimental.

I also want to acknowledge the broader web of human and more‑than‑human factors that made this work possible: the companies who created the software that allowed us to run the course online; the land mined for the materials used to produce the hardware; the people, plants, and animals displaced to make way for those mines; and the transport systems that brought these materials into my reach. I am indebted to the ancient life forms that became the fossil fuels powering this system, and to the future generations who will live with the consequences of my choice to create and share these ideas.

More like this

-

Hamsters, Dark Matter and the Practice of Practice

What we learned from designing and hosting the course ‘Climate Adaptation for Creatives’Dr Natalia Eernstman,…

-

THE FUTURE IS HEALTHY AND NUTRITIOUS – HERE’S HOW TO MAKE IT HAPPEN

As food security rises on the global agenda, the solution isn’t stockpiling but transforming our…

-

Training for a Changing World

As the challenges facing our natural world grow more complex, the need for skilled, adaptable…

The BMC Prospectus

Download the Black Mountains College prospectus for an overview of our courses, campuses, and vibrant student life

Visit us

Come along to one of our Discovery Days or Campus Tours to explore our campuses and meet your tutors